Deep Learning inference framework using native Python

You may be the brain but software frameworks have always been the brawn behind development and sucess of deep learning algorithms. Frameworks tike Tensorflow, Caffe, Torch, Theano, etc. do most of the heavy lifting by abstracting out the time consuming and difficult task of coding the routines necessary for development. In this post, as a tribute to all the awesome engineers working towards the development of these frameworks, we shall implement a very small scale deep learning inference framework in python. I came across something like this while I was taking the Python for Machine Learning course in Udacity. I added more functionality to make it look like a complete framework very similar to tensorflow :-)

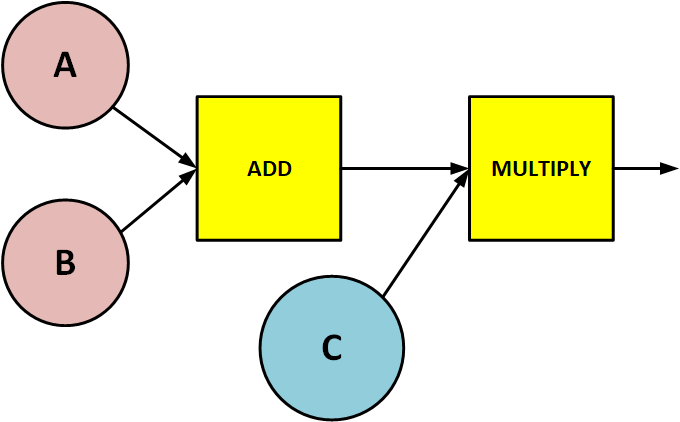

Lets start with a very simple example. Consider the graph below (we shall call it GRAPH_ABC).

Suppose as-per our design requirement we want that in GRAPH_ABC:

- A and B to be supplied from outside when we execute the graph

- C to be a variable defined inside the graph

- ADD and MULTIPLY as operators operating on A, B and C

In Tensorflow’s terminology:

- A and B are

placeholders - C is a

variable - ADD and MULTIPLY are

operations

GRAPH_ABC can be easily constructed with the following code:

import tensorflow as tf

A = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, name='a')

B = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, name='b')

C = tf.Variable(1.0, name='c')

y = tf.add(A,B)

z = tf.math.multiply(C,y,name='z')

with tf.Session() as sess:

sess.run(tf.initializers.global_variables())

feed_dict = {A: 1.0, B: 2.0}

result = sess.run(z, feed_dict=feed_dict)

print result

feed_dict = {A: 1.5, B: 2.5}

result = sess.run(z, feed_dict=feed_dict)

print result

Looking at this, we observe that in a typical tensorflow program, we need the following:

graphwhich defines what needs to be executed.placeholdersto accept new inputs (from external world) that are supplied during the execution.variablesto store intermediate tensors.operationsto operate on data in the graph.sessionin which the graph is executed.

Lets tackle each of these separately.

GRAPH

Graph is the superset container that contains all the operations, placeholders and variables. To make things simple, we will store all operations, placeholders and variables as separate lists in the graph object. The python code for this is very simple and straight forward.

class Graph():

def __init__(self):

self.operations = []

self.placeholders = []

self.variables = []

Lets go back to our GRAPH_ABC and take a look at the dependency relations between the various nodes in it.

- A, B and C don’t have any inputs

- ADD consumes the outputs of A and B

- MULTIPLY consumes the output of ADD and C

- Inputs of ADD are outputs of A and B

- Inputs of MULTIPLY are outputs of ADD and C

Without loosing generality, we can safely state that variables and placeholders do not have inputs. Operations can consume either variables, outputs from other operators or constants.

PLACEHOLDERS

Placeholders are for getting in new data. So at the start all we need to know is the shape of the placeholder and the actual data in it will be filled at the time of execution. So we create a class in which the constructor needs only the shape of it (shapes are critical when we can to determine sizes of intermediate variables based on other variables). Since its a node in the graph it will have an attribute called output_nodes to keep all the nodes to which this placeholder provides data to. Note that everytime we create a placeholder we append it to the list of placeholders in the graph object (em._default_graph).

Placeholders are nodes in the graph whose outputs are consumed by other nodes. So to keep track of the nodes which any particular placeholder feeds data, we add member variable list (self.output_nodes) to store all nodes connected to it. Since placeholders never consume any other node’s output, we don’t need anything member variables for inputs.

import emulator as em

class Placeholder():

def __init__(self, shape):

# Keep track of all nodes that are connected to this node

self.output_nodes = []

self._shape = shape

# After creating it, add the instance to list

# containing all placeholders in the current graph (_default_graph.placeholders)

em._default_graph.placeholders.append(self)

@property

def shape(self):

return self._shape

VARIABLES

Variables are objects whose value can be altered during execution. We need to provide them with an initial value aswell. As as we did before, anytime we instantiate a variable object we need to append it to the list containing all variables in the graph. Similarliy it will have an attribute called output_nodes to keep track of the nodes which consume its output. We will provide an additional method to allow loading values into the variables.

import emulator as em

class Variable():

def __init__(self, shape, initial_value = None):

"""

Constructor

"""

self._shape = shape

# Actual value of the variable. Initialize it with

# initial_value at the time of creation

self.value = initial_value

# Keep track of all nodes that are connected to this node

self.output_nodes = []

# After creating it, add the instance to list

# containing all variables in the current graph (_default_graph.variables)

em._default_graph.variables.append(self)

@property

def shape(self):

"""

API to get the shape of a variable

return type is python list

"""

return self._shape

def load(self, val):

"""

API to load values to a variable.

shape of the new value should be same as

the original shape of the variable.

Only supports numpy arrays as val.

"""

assert list(val.shape) == self._shape

self.value = val

OPERATIONS

Operations are responsible for modifying values in variables and placeholders to produce outputs. Here we will implement the base class for all operators. So methods like shape and compute which depend on the actual operation are to be implemented in the inherited subclass. Operators are associated with inputs (on which it operates) and outputs (nodes in the graph that consumes this Op’s output). Everytime we add a new operation node with a set of inputs nodes, we append this operation node to the list of output_nodes of each of the inputs (this will help us while traversing the graph and executing it).

import emulator as em

class Operation(object):

def __init__(self, input_nodes = []):

self.input_nodes = input_nodes

self.output_nodes = []

# For every node in the input, we append this operation (self) to the list of

# the consumers of the input nodes

for node in input_nodes:

node.output_nodes.append(self)

# There will be a global default graph (TensorFlow works this way)

# We will then append this particular operation

# Append this operation to the list of operations in the currently active default graph

em._default_graph.operations.append(self)

@property

def shape(self):

raise NotImplementedError('Must be implemented in the subclass')

def compute(self):

"""

Must be implemented in the sub class.

"""

raise NotImplementedError('Must be implemented in the subclass')

Lets take a look at an example op. He shall implement elementwise add operator. We have put the Operation class in emulator module.

from emulator.operation import Operation

class add(Operation):

def __init__(self, a, b):

super(add, self).__init__([a,b])

self.shape = a.get_shape()

def compute(self, var_a, var_b):

self.inputs = [var_a, var_b]

return var_a + var_b

SESSION

We run session with any node in the graph (whose value we want) and a feed dictionary with the values of the placeholders we want to execute the graph with.

In session.run method, we first create a list of nodes obtained by doing a post order traversal of the graph starting at the output node. Essentially, this creates a list of all nodes (in proper order) that we have to execute to get the output of the required node. It does so by recursively appending nodes and their inputs to the list. For placeholders, the node output is obtained from the feed_dict. For variables, the node output is obtained using node.value memeber variable. For operations, we execute node.compute(node.inputs) to get its output value.

import numpy as np

from .operation import Operation

from .placeholder import Placeholder

from .variable import Variable

class Session:

def traverse_postorder(self,operation):

nodes_postorder = []

def recurse(node):

if isinstance(node, Operation):

for input_node in node.input_nodes:

recurse(input_node)

nodes_postorder.append(node)

recurse(operation)

return nodes_postorder

def run(self, operation, feed_dict = {}):

nodes_postorder = self.traverse_postorder(operation)

for node in nodes_postorder:

if isinstance(node, Placeholder):

node.output = feed_dict[node]

elif isinstance(node, Variable):

node.output = node.value

else:

node.inputs = [input_node.output for input_node in node.input_nodes]

node.output = node.compute(*node.inputs)

if type(node.output) == list:

node.output = np.array(node.output)

return operation.output

Using this template, you can add more ops like conv2d, pool, etc. If you have any custom hardware accelerator, you can model layer execution using similar method and check networks performance. Check out my github repo for complete implementation.